CIDE (2007) Doumat

Online ancient documents in European national libraries, a survey

|

Sommaire

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Studied European libraries

- 3 The survey

- 3.1 Site objectives

- 3.2 Languages

- 3.3 The Number of documents online (Digital library)

- 3.4 Document type

- 3.5 Access fee

- 3.6 User type

- 3.7 The personalization of the information

- 3.8 Discussion space

- 3.9 Real time help

- 3.10 Search metadata

- 3.11 Thesaurus

- 3.12 Image annotation

- 3.13 Interfaces

- 3.14 Site creation date and site updating date

- 4 Conclusion

- 5 Références bibliographiques

.Résumé : Dans ce papier nous présentons notre étude des sites web de 45 pays Européens. Nous participons à un projet qui vise la mise en ligne des trésors du musée de la ville d’Alep en Syrie. Ce musé dispose de manuscrits, sculptures et des documents audiovisuels. Afin de pouvoir définir les critères et le cahier des charges pour ce projet nous avons décidé d’étudier ce qui se fait en Europe dans ce domaine.

- Keywords

- digital libraries, national libraries, online archives, comparison, survey

- Abstract

- In this paper we present our survey of the websites of 45 European countries. We focus our study on the availability of online digitalized ancient documents. We are working on the on line publication of digital reproductions of the treasures of Aleppo city museum in Syria. The objects have many types and their digitized reproductions cover a large range of media types (images, text, sounds, and video). In order to be able to put down the major guidelines of our system we decided to study the web pages of the European national libraries.

}}

Introduction

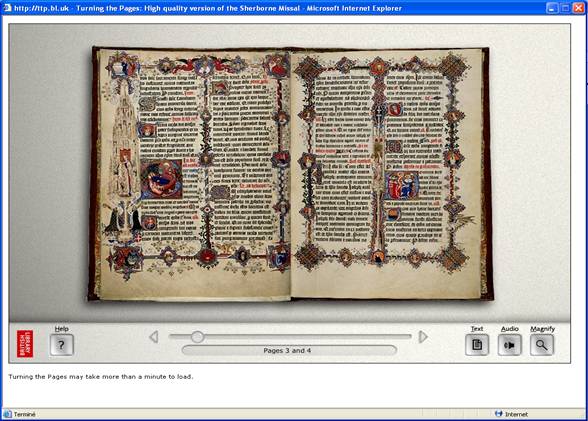

A large quantity of precious historical, cultural, and modern information exist in libraries, thus, to protect these cultural and historical treasures from being lost, and to make the whole information available to the public, they have to be put on the Internet. For that reason, many libraries have made web sites to publish digitalized books, images about rare books, facsimiles of the manuscripts and valuable pictures; or about historic sound and video registrations besides the books, periodicals and other documents. Nowadays millions of objects are being made available to the general public that were once only the province of the highly trained researcher. Students and researchers have unprecedented access to illuminated manuscripts, art, music sheets, photographs, architectural drawings, ethnographic case studies, historical voices, video, and a lot of other rich and varied resources in a digital form. Perseus Project [15] concentrates on digitizing the cultural heritage of Greco-Roman collections because they become more valuable as the past recedes. Accessing documents through the websites is often more simple and rapid than searching them in the library’s building. As [17] state, the issues of a digital library (DL) are as well preservation as access, outlined a framework for the development of digital libraries by proposing that DLs need to move beyond the “paper-based metaphors” that privilege the finding and viewing of documents to support new ways of doing intellectual work .Websites frameworks allow to expose digital images of rare and old protected documents that are not available as originals for the public, for instance users now can turn pages of ancient manuscripts in a realistic way (Figure 1 http://www.bl.uk/ttp2/ttp2.html).

The emergence of the World Wide Web has given the opportunity to libraries, museums, universities, national or international projects, and other organizations to make their electronic contents of ancient or recent documents available to a growing number of users (researchers, humanists, scholars…) on the Web.

We are working on the on line publication of digital reproductions of the treasures of Aleppo city museum in Syria. The objects have many types and their digitized reproductions cover a large range of media types (images, text, sounds, and video). In order to be able to put down the major guidelines of our system we decided to study the web pages of the European national libraries. We choose these sites in order to have a representative and finite set of online libraries.

While access to online resources was greatly improved in the last decade, online archive and digital libraries are still remaining difficult to be used, particularly for students and beginner users [17], [11]. In [18], the authors work on building an information context around digital library resources and services; they aim at integrating the user participation in the creation of this context to facilitate information retrieval.

How we studied the websites

Many studies were done on web sites in general to evaluate them and put criteria for the best performance and usage. Some of them concern the libraries themselves: [10] publishes results online when comparing libraries in the USA depending on their geographical locations, sizes of their collection, services, organizational characteristics and other options.Others study the online digital libraries focusing on their ergonomics and technological solutions. In [14] authors propose three features to characterize a successful digital library design (finer granularity of collection objects, automated processes, and decentralized user contributions).

There are a lot of studies on web page usability; in general web sites’ quality depends on many criteria [1]:

- Usefulness: the user waits that the site furnish him the services that he needs

- Legibility: the pages have to be clear, easy to be understood and to be downloaded

- Navigation: the site structure must be adapted to the logic of the user depending on his needs, and not on the internal organization of the data on line

- Objectivity: the information have to be presented without marketing effects, and have to be exploited functionally

- Reactivity: the user needs to get the information quickly, in order not to waste his time

For all these reasons, many ergonomic metrics were founded to evaluate the websites and to overcome their problems, in order to help the users to get what they want rapidly. The ergonomic evaluation consists of testing the website components to fix the usability problems; there are different criteria for the evaluation (Gary Perlman [8], Dominique Scapin [5], and ISO Metrics [1]). In the same concept, the following checklist, from IBM Web Design guidelines [9], allows to identify the main usability problems of a web site:

- Is the purpose of the site clear?

- Does the site clearly address a particular audience?

- Is the site useful and relevant to its audience (public)?

- Is the site interesting and engaging?

- Does the site enable users to accomplish all the tasks they want or need to accomplish?

- Can the users accomplish their tasks easily?

- Does the information (content) and the order in which it is presented (organization) suite the purpose?

- Is the important information easy to find?

- Is all information clear, easy to understand and easy to read?

- Do you always know where you are, or how to get where you want to go?

- -Is the presentation attractive?

- Do the pages load quickly enough?

All these metrics centered on the agronomy of the websites in general, whereas in [19], the author posed some suggestions of how digital libraries should be designed from user’s perspective. Digital libraries should be able to offer users rapid information search, the access to important features of the original media, the interaction with other users or librarians, the ability to share and annotate documents and to support collaborative knowledge exchange and emergence.

Our study focuses on the online digital documents that are available on the European national libraries’ sites and the services around them. And we are especially interested in the digital archive that represents the cultural heritage, more than the digital libraries of recent documents. For this reason we have grouped the previous criteria about the digital library design, Websites’ quality, and ergonomic metrics together, we have used some of them and proposed others, to obtain the following list of our proper criteria:

- What are the main objectives of the website?

- Is the site presented in different languages versions?

- How many online documents are available?

- What types of media have been digitized (manuscripts, tapes, sculptures…) and how they are been presented on the websites (text, images, videos)?

- Financial model of the site (free, payment based)?

- Different user profiles?

- Does the site permit users to personalize the obtained information?

- Does the site offer a discussion space between users or between users and librarians?

- Does the site provide assistance (real time hints, expert contact, and chat with a librarian …)?

- Does the site contain search tools?

- Does the site include thesauri?

- Does the site provide image annotation tools?

- Are the site interfaces clear and do they care about the different users’ types?

- Are site creation date and pages updating date obvious?

The elements of this list will be detailed in the following sections. We apply these criteria on the websites of the national libraries of the European countries to measure their performance and their usage facility.

Studied European libraries

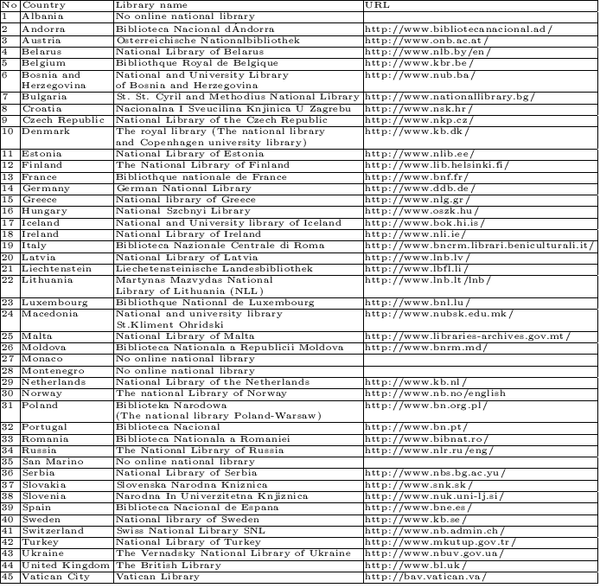

In our work, we gathered a list of 45 websites of European national libraries we organized these sites in an alphabetical order in the (Table 1). All these sites were visited in January 2007.

Table 1.: European national libraries websites

The survey

In this section we present the results of the evaluation:

Site objectives

We can summarize sites’ objectives in: “Registration, protection and access to national electronic resources on the Internet”

Several countries are creating their own digital national archives to ensure the preservation of contents of historical relevance to their cultures. In addition, libraries aim to provide information about the country printed publication, and about the publication that printed abroad in the country language, the works that are translated to other languages, and the publications about the country in foreign languages.

Besides offering information about their collections, the sites work also to adapt many services to the needs of the users: like ordering items from the library (documents copies, micro films…).

Languages

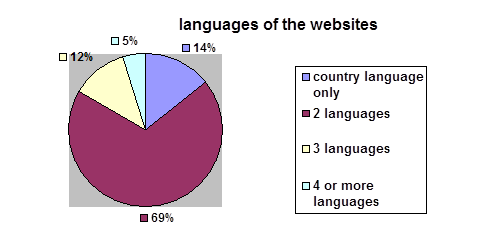

The adaptation of the site pages to native language and to other languages for the foreign audience is one of the important quality indicators of websites. According to our work, we couldn’t understand the contents of many sites, because they were presented in just the country language, which is not well known like (Slovak, Romanian, Moldavian, Croatian, Portuguese…). Fortunately most of the sites are presented in more than one language, however, we noticed that some of them don’t furnish the same information in the different versions of the website; usually the national language version includes more information, for example, the National library of France['Table 1'{13}].

Moreover, we realized that lot of sites needs management for their Multilanguage; for instance, many sites have English version but the research tools and other information are in the original language; as the sites of (Austria Table 1{3}, Belarus{4}, France{13}, Germany{14}, Hungary{16}, Italy{19}, Norway{30}, Serbia{36}, Slovenia{37}, Spain{39}, and Vatican City{45}).

The English has great importance and it is the dominant language in the websites that we had studied; we noticed that 80% of the sites use it as first or second language. For the other languages, 16% of the websites contain a French version, and a weak percentage of 1% for the Russian, German, Spanish, and Italian languages. Figure 2 represents percentages of websites’ languages of the analyzed European international libraries sites.

The Number of documents online (Digital library)

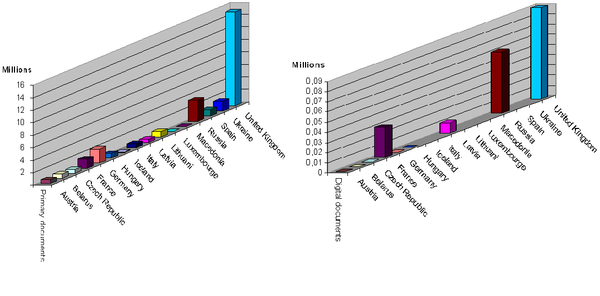

All the libraries include between thousands and millions of volumes, documents, periodicals, and objects (music sheets, sound records…). However, the problem is that not all these documents are digitized and have been put on the library’s website for users’ availability. There are just a few sites that offer this option, like the website of the British library ['Table 1'{44}], it contains online catalogues, documents, and exhibitions; moreover the site gives brief information about the library and its collections, it is also rich in electronic documents and contains over 90,000 images and sounds. Russia’s national library ['Table 1'{34}] site has an online exhibition of photos and images; in addition to a digital library that provides access to electronic materials; the site includes a table of the library’s holdings as well as the quantity of each item; this site also mentions the amount of its digital documents which is about 60594 documents.

Latvia’s national library ['Table 1'{20}] provides a digital library of ten thousands newspapers, graphic documents, maps, e-books, scores, sound recordings in its digital collections. France national library (BnF) ['Table 1'{13}] has 15 million documents in its collection, but the number of documents online is less than 30000 documents. In addition, the library has a project to archive the French web, in this project the library is interested in determining the French websites existed on the entire web and not archiving the French documents [12].

Some of the websites that we have examined contain a certain type of electronic documents as magazines, maps, newspapers, post cards, references, daily or monthly papers, sound recordings, or e-books; but they don’t give any information about the number of these digital documents, like the websites of the following European countries (Estonia ['Table 1'{11}], Iceland {17}, Lithuania {22}, Luxembourg {23}, Malta {25}, Norway {30}, Serbia {36}, Spain {39}, Sweden {40}, and Vatican City {45}) We want to mention that on the site of National library of Sweden [Table 1{40}] we found digitized collections from some examples to complete works.

The Vatican library website ['Table 1'{45}] presents the Vatican treasures plus the secret archives that are talking about the private archive of the pope (the secret archive of the Gonzagas, the Estensis, the Montelefeltros, etc.). Furthermore, we observed that many libraries’ websites don’t provide electronic documents, or even information about the library’s contents from collections and catalogues, as the sites of (Macedonia ['Table 1'{24}], Slovenia {38}, Turkey {42}, and Ukraine {43}) In Figure 3 we see the numbers of the primary documents in European national libraries and the number of the digital documents in their websites (for the sites that mentioned to their document collections quantity).

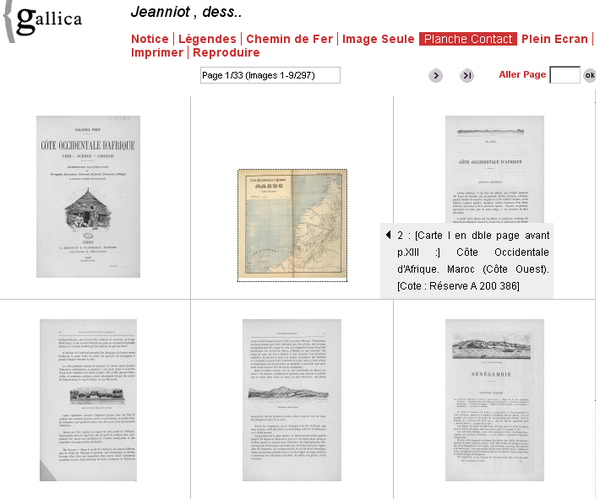

Some sites offer links to other digital resources of the same country, to get the documents online as in the National library of France that gives link to GALLICA (La bibliothèque numérique de France[7]) ; this last contains the digital collection Figure 4.

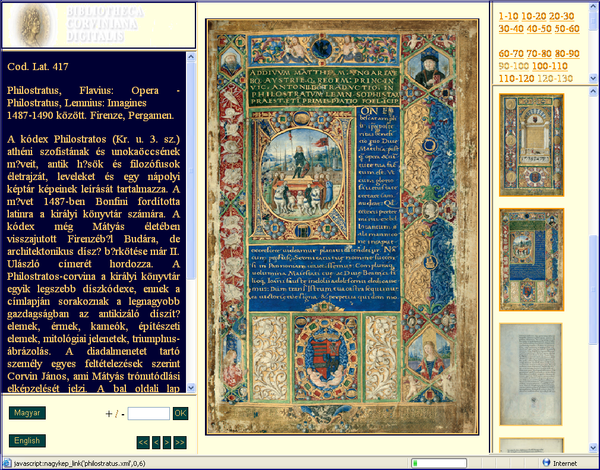

Another example is the site of the national library of Poland; it contains BNpolona [2] for the documents online with the ability to browse them in mosaic besides enlarging the photos. The national library site of Czech Republic ['Table 1'{9}] gives a link to digital resources [3] that contains facsimiles of the medieval manuscripts. Hungary national library website ['Table 1'{16}] also contains collection of digital documents about old books as in Figure 5

Luxembourg library ['Table 1'{23}] has a project to digitize its documents; the project is called: Luxembourg online and contains more than 55000 pages and 18000 historic post cards; when we visited the site of Luxembourg national library, we found the postcards online as thumbnails.

British Library ['Table 1'{44}] is the unique library that offers browsing rare and old books in 3D as shown in Figure 1, in addition users can see an explanation about the viewed page or listen it.

On the other hand, the sites that are presented only in their national languages (not in English or French) may contain online digital documents that we had missed.

Document type

Documents stored in libraries are original documents and could be also considered as primary documents, they exist in two types: either in 2D like paper and leather documents (papyrus, incunabula, manuscripts, maps, printed music, graphics, albums, drawings, cartographic documents, atlases …) or in 3D as tablets, coins, medals, engravings, statues, other art materials. The most important in the digital library is to make digital copies of these original ones, which are obtained either by scanning primary documents or taking digital photos in a special technique, like in the InscriptiFact project [13] where authors use a digital camera and many flashes attached to a computer to take digital images of the 3D objects. The digital copies of the primary documents would be distributed on the Internet.

The costs and complexity of the preservation of documents increase with the variety of media types archived and it may become unbearable. Hence, website administrators focus their efforts on the preservation of documents with a selected set of media types (HTML pages, PDF, doc, and XLS files, JPEG, GIF and TIFF images) representing copies of real documents. So we found that some sites illustrate their contents (books, manuscripts…) with small images or thumbnails and grant the ability to enlarge them in a higher resolution as in the sites of (Malta {25} , Belgium {5}, and Hungary {16}) national library as in Figure 5.

Another type of document provided by the website is audio files. In the British library website the sound archive provides free public access to its collections of recorded sound. The website contains hundreds of spoken word recordings exhibiting a wide range of English accents and dialects in addition to rare recordings from the world and traditional music collections. Conversely, we did not find video files in the websites that we had examined.

Access fee

Access fee is the access that goes beyond search interfaces to the ability of users to retrieve information in the form that it can be read, viewed, or otherwise employed constructively. Access thus goes beyond the ability to link to a network [17]. An access fee is charged to libraries and institutions to cover the costs of maintaining a digital library, such as use of search capabilities and related Web-based features. The access fee can be paid as a one-time charge for ongoing access to the e-book title, or can be paid on an annual basis; many sites give a price-list of registration, services, photography and items reproduction, like the sites of (Sweden['Table 1'{40}], United-Kingdom {44}, Slovenia {38}). For electronic resources there are many degrees of access to digital documents.

- "Open access" or “Free access” means that documents are available freely to the Internet public, permitting any users to read, download, copy, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles. The only constraint is on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited. [6] In practical terms, open access to e-prints currently means free access. An example about the free document access is the documents of the Luxembourg and British library.

- Other sites make their documents payable or need an “access pass”. In the Netherlands national library site, users have free access to books, journals, CD-ROMs, e-journals and databases without pass; however they need an access pass to see more options.

- Some libraries reserve the access to their databases to their employees and the registered users by offering them a password for a site access; as an example, users need (ID& password) to see the electronic magazines on Estonia’s website.

User type

The web sites of the European national libraries could be of interest to a community of users, for instance:

- Students who use the Net as a primary source of information

- Researchers who seek finding certain information in the libraries

- Publishers who contact the national library to obtain ISBN for the new published books

- Librarians also who use the site to answer users’ questions or to add new resources

We can consider these users as customers. Another type of users could be visitors that visit the site by curiosity or to have a look.

Some websites think about a special type of users like children, the website of the national library of Serbia['Table 1'{36}] contains “Serbian children’s digital library” that furnish e-books for children to enable them read what they want on their site. British library precise in its website ['Table 1'{44}] the services for each type of users, it contains services for researchers, business, and for the library and information professionals. Also, the site opens its online gallery to everyone to see library’s treasures and images of London buildings. Special resources are included in the website for learners and teachers.

The personalization of the information

A digital library provides an important information environment to retrieve and refer to appropriate information directly online. Different library’s users will have different personal requirements and interests in the use of library materials. Hence, personalization is an essential service that should be provided to users to allow them to create their own personalized information environments. As an example the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN) [16], which is a commercial digital library, it has an interface to allow users to develop resource applications for them, then user information would be stored on SCRAN’s server to work anywhere and not just on the local machine. In [14] authors mention that digital libraries have to be able to analyze users’ behavior and their background, to offer new automatically generated configurations of information.

In the Estonia national library website ['Table 1'{11}], the user could be registered in the website database then he will receive information about his needs by using My Ester, which provides the user with regular information about his demanded books, if they are available or borrowed. However in the other studied website, these options are not available.

Discussion space

Digital library is not only an information resource where users may submit queries to satisfy their daily information need, but also a collaborative working and meeting space for people sharing common interests. They let the user discuss with other users or with the librarian about resources, discussion space could be represented in chat option, like the one that is offered by the website of the national library of Netherlands ['Table 1'{29}]

Real time help

Help in the libraries websites is the ability to allow users direct contact with library staff, via telephone number, fax number, e-mail, and chat room; to help him find his requirements. Furthermore, some websites offer the user the capability to ask librarians questions, besides giving examples about the questions, selecting the theme of the question for a better answer, as in the site of the France national library.

Some sites don’t give the user any information in case he wishes to contact the library, like the site of Poland national library ['Table 1'{31}].

Another type of services (or help) is Alerts: which are information sent by the library to a subscribed user, who is carrying out long-term work on a topic, about certain publications relating to his field. Alerts are provided by the site of Swiss national library ['Table 1'{41}].

Search metadata

Metadata helps users to identify, describe, and locate what they need from the digital resources on the Internet sites. Many different metadata formats exist, some of them are quite simple in their description, and others are complex and rich.

Even though access by specialist scholars and educators to digital objects has grown at an exponential rate, there is an important factor have prevented them from fully taking advantage of these resources in the absent of the search tools in some websites.

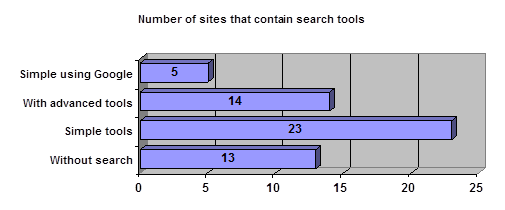

we noticed that many libraries sites don’t provide users with search metadata tools, most of the websites are supported with a simple search tools to permit the user perform his research by writing some keywords, many sites are equipped with advanced search tools that demand the user about some constraints like title, author, period, publisher, etc; for an express and précised research. Some libraries comprise the Google search engine in their websites, either that they don’t have special search tools, another reason that they use the Google tools as an advanced technique to search in their databases and websites, or because that they want to enlarge the search of the user on the whole web.

Figure 6 shows the number of the studied sites that contain search tools, note that a site can have different search tools at the same time.

Thesaurus

A thesaurus is a tool for vocabulary control. By guiding searchers about which terms to use, it can help to improve the quality of retrieval

Including a thesaurus in the website gives it the

- Capacity to auto correct user’s keywords of research

- Gives the detailed categories of each catalogue on the site

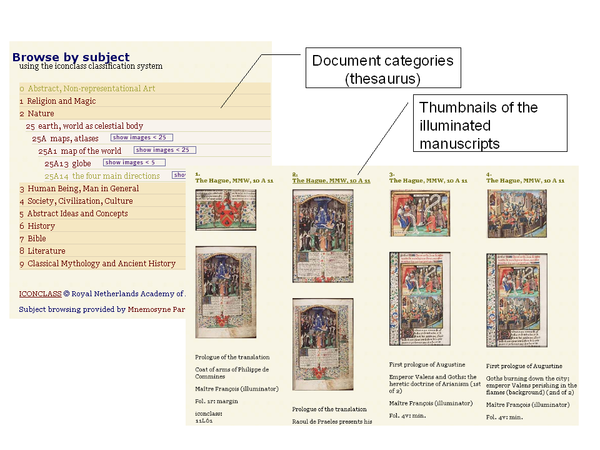

Netherlands National library website ['Table 1'{29}] contains link to digital collection of medieval illuminated manuscripts library, with a detailed thesaurus [4] Figure 7

In the Andorra’s national library website ['Table 1'{2}], the thesaurus facilitates the search and enlarges it, when it enables the user to write just the beginning of the keyword to obtain more results about his search; whereas in the Iceland and British libraries’ websites ['Table 1'{17}, {44}], the thesaurus sorts the databases depending on its subject to help the user in his research.

Image annotation

Even though users have a long history of researching archives and are comfortable sifting through records and locating items, they need to make annotation, comparisons, and summaries, these processes are not yet translated into online tools. Contemporary bibliographic tools have expanded to allow users to catalogue and keep notes about media, but they do not allow users to mark specific passages and moments in multimedia, and return to specific places at later time [17]. Consequently, all the sites that we had studied don’t provide image annotation tools.

Interfaces

Interfaces have a great importance in exposing the contents of the site, and to guide the user in a logic steps to achieve what he needs easily and quickly. Most of the sites have a layout conceived only for one screen resolution so the font size is too small most of the time, and thus the site difficult to read. The National library of Norway (30) and Slovenia (38) provide on their web site the ability to enlarge the font size for the “Visually impaired persons”. The site of British (44) library provides an audio version of the text explanation, while the Serbian (36) national library has a special section for children.

Site creation date and site updating date

Creation date of the site shows if the site has been recently put on the Internet or it serves the users since long time. Some sites, about (31%) of the studied sites, include the creation date of the site, and rarely (1%) the updating date of each page in the site (Estonia’s national library site ['Table 1'{11}] contains the updating date of most pages as well as the national library of France ['Table 1'{13}] and Swiss national library['Table 1'{41}] sites). By looking at the updating date, the user can realize if the information on the web site are recently modified, or if they exist on the site since the creation date without any modification.

Conclusion

Our survey gave us a list of guidelines and features to keep in mind for ”living online archives” in general and for our Aleppo archive project in particular. These features are:

- Be simple, adaptive and personlaizable in the user interface.

- Provide equivalent multilingual interfaces, but at least an English version.

- Publish as many documents as possible online, in a digital version.

- Present clearly the creation and update date on the website.

- Handle multimedia documents through multimedia interfaces.

- Provide simple and advanced assisted search tools. Guide the user.

- Include multi modal navigation and exploration facilities (thesaurus, ontology, colour, date, metadata ...).

- Indicate clearly different contact information (librarians, experts, commercial service, helpdesk...)

- Incite and support user participation in document annotation (text and image annotation features).

- Provide a collaborative working, discussion and discovery space for people sharing common interests.

As a next step, we intend to create an illustrated model of a ”living online archive”. As an online archive, it must provide through a web-based system, access to digitized reproductions of ancient artefacts. As a ”living archive” it should provide a highly interactive platform to the users with evolved assistance facilities. This model, methods and prototype software components are to be reusable in further digital archive projects.

Therefore we are interested in our work to generate two versions of the site: in English and in the original language (the Arabic). In Aleppo museum’s website we will deposit images and video documents about the existed objects. Moreover, we aim to provide different research tools besides a thesaurus for various types of users (curious people who visit the site by chance, historians, researchers…). In addition, we intend to create a user discussion space which enables information exchange and a space for image annotation.

Références bibliographiques

[1] ↑ http://www.usabilis.com/gb/usability_engineering/ergonomic_evaluation.htm

[2] ↑ http:// www.polona.pl ; (BNpolona)

[3] ↑ http:// www.manuscriptorium.com ; (Medieval manuscripts by the national library of Czech Republic)

[4] ↑ http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/index.html ; ( Medieval illuminated manuscripts)

[5] ↑ http://www.inria.fr/personnel/Dominique.Scapin.fr.html

[6] ↑ http://www.digital-scholarship.com/cwb/OALibraries2.pdf

[7] ↑ http://gallica.bnf.fr/ ; (Digital library of France)

[8] ↑ http://www.acm.org/~perlman/question.html

[9] ↑ http://www-3.ibm.com/ibm/easy/eou_ext.nsf/publish/572

[10] ↑ http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/libraries/index.asp

[11] ↑ }W. Y. Arms, Digital libraries, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2000.

[12] ↑ S. Abiteboul, G. Cobena, J. Masanes et G. Sedrati, "A First Experience in Archiving the French Web". ECDL 2002, LNCS 2458, page(s) 1-15, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2002

[13] ↑ L. Hunt, M. Lundberg et B. Zuckerman, "InscriptiFact: A virtual archive of ancient inscriptions from the Near East", International journal on digital Libraries, volume5, number 3, May 2005. pages 153-166.

[14] ↑ G. Crane, D. Bamman, L. Cerrato, A. Jones, D. Mimno, A. Packel, D. Sculley et G. Weaver, "Beyond digital incunabula: Modeling the next generation of digital libraries", ECDL’06 pages 353-366

[15] ↑ G. Crane et C. E. Wulfman, Towards a cultural heritage digital library. Presented at ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL 2003), Houston,TX, 2003, pages 75–86..

[16] ↑ G. Chowdhury, D. McMenemy et A. Poulter, "Large-scale impact of digital library services: Findings from a major evaluation of SCRAN". In ECDL 2006, pages 256–266.

[17] ↑ D. Rehberger, M. Fegan et M. Kornbluh, Reevaluating access and preservation through secondary repositories: Needs, Promises, and Challenges. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, ECDL 2006, LNCS 4172, page(s) 39 – 50.

[18] ↑ C. Lagoze, D. Krafft, T. Cornwell, D. Eckstrom, S. Jesuroga et C. Wilper, "Representing contextualized information in the NSDL". In ECDL 2006 , pages 329–340.

[19] ↑ A. Blandford, Understanding users’ experiences: evaluation of digital libraries. DELOS workshop on evaluation of digital libraries, Padova, 2004. Page 31-34